Speaking with a Manager

The Mid-Atlantic is out of dependable power. Now, PJM governors have escalated their complaint straight to the White House

Last Friday, a troika of mid-Atlantic governors showed up at the White House for a surprise visit. Not long after, they were gone, just in time for forecasts of Winter Storm Fern to underscore the stakes of a grid stretched to its limits.

What pushed them there? Start with PJM’s latest capacity auction.

The bottom falls out at PJM

In mid-December, PJM ran its annual capacity auction. This auction is supposed to answer a boring question: three years from now,1 will there be enough firm capacity on the system to serve peak demand?

During weeks like this one, where an extended cold snap has triggered Energy Emergency Alerts around the country, we can see why sufficient capacity on the grid is so important. And according to PJM’s recent report for the 2027/28 delivery year, the region is coming up soberingly short.

For the first time in its history, PJM reported that the whole RTO has failed to meet its reliability requirement; it procured about 6.6 GW less than what was needed to meet PJM’s Installed Reserve Margin—the margin of safety included for reliability. PJM emphasized that clearing short of the reserve margin does not mean for certain that there will be outages, but “maybe” is not exactly a reassuring turn of phrase when it comes to blackouts.

Meanwhile, PJM’s report lists a whopping clearing price of $333.44 per MW-day. That makes it the third straight auction to set a new record price, which has risen by over one thousand percent compared to three years prior.

The situation is under [price] control

What’s more, this number has in fact been significantly suppressed by the fact that a recent FERC-approved settlement imposed a temporary “price collar” (a cap and a floor) on PJM’s last two auctions. That collar was the product of pressure from governors in PJM states, who argued that consumers were headed for an avoidable price spike while PJM struggled to find a lasting fix.

We know what the market-driven price would have been, though, as PJM published a “no cap-and-floor” counterfactual for the same auction. In that scenario, the clearing price would have been roughly $530/MW-day, meaning that the reality of our supply constraint is even worse than the headline.

This constraint should concern ratepayers. If PJM is genuinely short on firm capacity, suppressing the clearing price can also suppress the incentive for new supply to enter (or for existing resources to stick around) at a moment when the system desperately needs more.

Loudest among the leaders arguing for the price cap was Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro, who first pushed the idea in 2024. Shapiro has emerged as something of a national leader (as well as a likely presidential candidate), and others across the region are following his lead.

Indeed, affordable energy has been the biggest issue on the ballot in some states, arguably deciding races like New Jersey’s gubernatorial win for Mikie Sherrill late last year. It’s no surprise then that in response to this crisis, Democrats and Republicans alike might grasp for a bigger lever and take this issue to the White House. In fact, that’s exactly what several governors did last week.

Governors take PJM problems to Washington

On January 16, Governors Josh Shapiro (D-Pa.), Wes Moore (D-Md.), and Glenn Youngkin (R-Va.) convened with the Trump administration to announce an unusually direct intervention into PJM’s market design. Notably, one key stakeholder wasn’t in the room for the announcement: PJM itself.

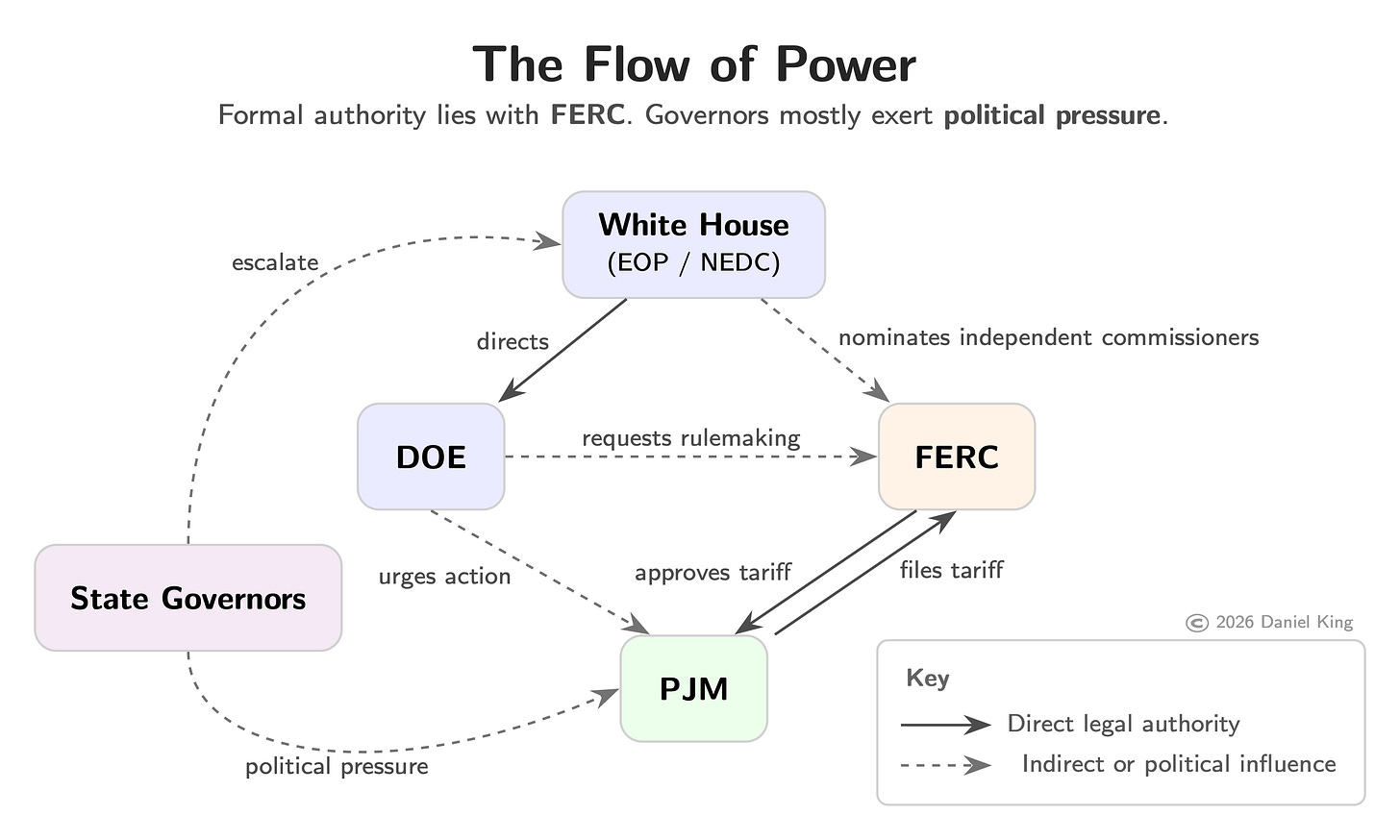

Why did these governors—including prominent Democrats who have made hay out of pushing back against the Trump administration—go to the White House? Because governors can’t order PJM to change its market rules, since PJM’s tariff lives under federal jurisdiction. All action must run through FERC. For instance, PJM must first make a filing at FERC, or FERC itself must launch a proceeding. A White House intervention is a top-down way to force action.

According to a DOE fact sheet that followed the talks, the White House’s regulatory push has two marquee components.

Extend the region’s price collar on capacity.

This one is pretty straightforward: the plan is to prolong the price cap and floor in effect at PJM.Create a 15-year procurement pathway for new power plants.

This is more novel. The administration is urging PJM to “accelerate development of reliable power generation by providing 15-year revenue certainty for new power plants.” Traditionally, PJM has held its capacity auction three years ahead of the year being targeted. But even with a multi-year lead, the capacity auction’s timeline is too short to reliably bring major new plants online. Generation companies can easily take over a decade to finance, plan, build, and launch a whole new power plant. The one-time emergency auction that DOE proposes would provide a long-term contracting tool on a 15-year term, creating an additional incentive for new build, atop PJM’s annual rhythm of capacity commitments. In the long run, the goal is to make Mid-Atlantic electricity more “reliable and affordable” by “building more than $15 billion” of new reliable baseload generation.

You compute, you pay in full

How do they propose paying for that new build? Per DOE:

“Require data centers to pay for the new generation built on their behalf—whether they show up and use the power or not.”

It’s a big deal. Here, DOE is not merely calling on data centers to contribute to meeting their electricity demand, which many a hyperscaler press release has reassured the public they already do. Rather, it’s something far more aggressive.

Consider the status quo. Suppose that a region scrambles to procure and finance new capacity because it expects a 5-GW wave of compute campuses. If 3 GW of those campuses are delayed, or if they use only 2 GW of the steel in the ground that’s been laid, households still get the bill for all 5 GW. But by tying data centers to pay “whether they show up…or not,” DOE is forcing seriousness on the part of developers: if you want PJM to treat your computing needs as real enough to justify new plants, you should be on the hook.

The price collar constrains supply

The push that Governor Shapiro led—and DOE has now extended—to put a price cap on capacity is a rational political response. When prices jump, households and small businesses pay. A price control can relieve that pain, buy time, and let political leaders say, credibly, that they took some sort of action to protect ratepayers.

But it’s a band-aid solution, and that palliative quality is precisely the problem. In a capacity market, high prices are the mechanism by which the system rewards more supply. If PJM is telling you it’s short on firm capacity, then suppressing the clearing price suppresses the incentive to build the next marginal megawatt. It makes today’s bill less painful to open but tomorrow’s shortage harder to solve. Thus, there is a tension between DOE’s proposal to (1) extend the price collar but (2) incentivize $15 billion in new reliable baseload power. The sole solution to PJM’s scarcity is more supply, and only the latter intervention can achieve that.

What happens next

Importantly, nothing announced at the White House changes PJM rules immediately. PJM market changes run through FERC’s oversight, PJM’s stakeholder process, and eventual tariff filings. And recall that PJM has plenty on its plate,2 even if it struggles to deliver competent solutions.

After chronic fumbles, PJM has its job laid out pretty clearly, and the market reform itself is once again in PJM’s court. The White House visit put the—biggest—political thumb on the scale. For state leaders, it’s fingers crossed.

Recently, PJM has been on a compressed auction cycle with a lead time of ~2 years.

The end of last year featured PJM’s own efforts at large-load integration and improved forecasting, plus a separate FERC action—discussed in our last issue—to concretize the treatment of co-located load in PJM’s tariff after the Commission found PJM’s existing co-location framework to be unjust and unreasonable.